When the Rain does not Rain

Summer has arrived in Namibia and with it, soaring temperatures.

The days here are excruciatingly hot and the sun shines with such ferocity that it seems to drain every ounce of my energy. When I walk around, I am perpetually dripping in sweat, my eyes are blinded by the brilliant sun that reflects light off of the endless sea of white sand and the swarms of flies and mosquitoes have found their way back into my bedroom.

You see, in Namibia, summer brings fierce sun, pesky insects and debilitating heat.

It also brings rains.

Yet, this year has been different.

This year, as my Namibian learners remind me on a daily basis “the rain has not rained.”

And so, as my hometown in Oregon is set to break rainfall records this year, my Namibian home is currently facing the opposite problem–its worst drought in thirty years.

Namibia is already one of the driest countries in the world. The barren landscape is home to both the Kalahari and Namib deserts and its unforgiving landscapes are susceptible to droughts. This year in particular, the severity of the drought has taken a devastating toll on the daily lives of most Namibians.

The majority of Namibians in the villages of the North are subsistence farmers.They rely on the Earth to provide their everyday needs and nourishment.

Yet, this year, the fields of millet encircling many of the homesteads in Onantsi have yellowed under the hot sun. The guava and mango trees have failed to bear fruit. The fields of crops have shriveled up and turned to dust.

When I arrived in my village last January, I remember seeing a soft dusting of green grass scattered across the endless sand sea. I remember watching the cows and goats as they munched on the shrubbery around my house. I remember standing in awe as I witnessed the dancing colors of the sunset as they painted their reflections on the seasonal lakes that mushroom with the yearly rains.

It all seems like such a distant memory to me now.

When I walk the sand tracks to my village these days, I see that the dusting of green grass has withered. The cows wander aimlessly around as though chasing a mirage. The seasonal lakes sit hollowed out and dry.

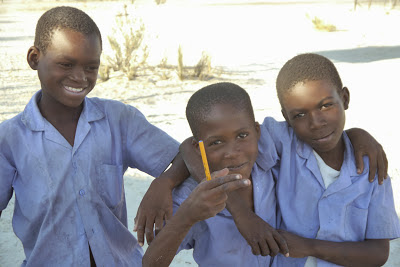

All around, livestock is dying, which means that many families are losing important sources of food. As a result, children often walk to school with little more than a bottle of water and, on a daily basis, I hear my learners shake their heads sorrowfully as they tell me that it has been a hungry year.

While I know I complain about Oregon’s abundant rain at times and while I acknowledge the inconvenience it often brings, I don’t think I’ll ever take the Oregon showers for granted again.

After spending nine months in one of the world’s driest countries, I have a new-found appreciation for rain.

With every cloud that graces the Namibian sky, my colleagues, learners and I hold our breaths, praying for the rains. But even the clouds seem to dry up and disintegrate in the presence of the African sun, as though they do not have the energy to put up a strong enough fight.

For my last two months in Namibia, all I can do is look to the skies and hope that the clouds will ultimately win the battle and that,for the first time in months, “the rain will finally rain again.”