How to Travel to Antarctica: The Land of Ice

For many avid travelers, Antarctica represents the ultimate adventure. A vast expanse of ice and snow, it is a land that is utterly uncompromising and hauntingly beautiful.

The silence of Antarctica is profound, broken only by the howling wind and crackling ice. It is a place where solitude reigns supreme, where it is either endless daylight or unbroken night. A place unaltered by human settlement and exploitation.

One that is both harsh in its extremes, and yet breathtaking in its purity.

Antarctica: The Great White Continent

Antarctica is nature at its most pristine. With its 5.5 million square miles of unexplored and mostly inaccessible wilderness, it is the last true frontier on Earth. Aside from a few thousand people stationed at research bases, Antarctica has no permanent residents. Ninety-eight percent of the continent is covered in ice.

I’d seen impressive glaciers during my travels in Juneau Alaska and Torres del Paine and El Calafate, but the quantity and scale of Antarctica’s ice sheets still blew me away. Massive ice fields—the size of which would be a highlight of travel itineraries elsewhere—were commonplace throughout the Antarctic peninsula.

I was completely unprepared for the continent’s superlative beauty, despite my high expectations. During my trip, I started to worry that the sheer beauty of Antarctica’s wilderness might hinder my ability to appreciate the beauty of other places (I’m pleased to say it hasn’t).

During the 2023-2024 season, a record-breaking 120,000 people visited Antarctica. That number is expected to grow in the coming years.

Yet, despite increased interest, travel to Antarctica is still far from mainstream. In fact, aside from the people on your ship, you’re unlikely to see anyone else during your visit.

One of the most remote corners of the globe, Antarctica represents the pinnacle of far-flung travel. As such, you’ll encounter a land that is as pristine as it was when the first explorers reached its shores.

A Brief History of Antarctic Exploration

The discovery of Antarctica is attributed to several people who gradually charted its icy expanse. While the continent may have been known to indigenous people and early seafarers, the first confirmed sighting came in 1820, by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev.

The interior of the Antarctic continent wouldn’t be penetrated until the early 20th century’s race to the South Pole between Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and British officer Robert Scott.

The race to the South Pole became a legendary story of exploration. Amundsen reached the pole in December of 1911, beating Scott by over a month. Tragically, Scott and his team perished on their return journey.

Today, though Antarctica’s geography is well known, the mysterious White Continent still draws adventurers who are seeking to experience its solitude and austere beauty.

Conquering the Seventh Continent

Antarctica was the last continent explored: both by humankind at large, and by me on a personal level. Touching down on the continent represented a monumental milestone in my travels. It was my seventh and final continent.

I’d wanted to book an Antarctic expedition for more than a decade but, as a budget traveler, the high cost of visiting gave me pause. It wasn’t until Dan and I decided to splurge on an epic honeymoon in lieu of a big wedding, that I felt I could finally justify the cost.

After all, why not celebrate our marriage with the most epic trip of our lives?

But Dan and I got married when Covid-19 hit, so we had to put our grand plans on hold. Then, we had our first child.

Finally, four years after we married, we left Elio with my parents for two weeks and set sail on a much-needed vacation.

Types of Antarctic Cruises

Antarctica has no commercial airports, public transportation, or paved roads. To reach the continent, you must join a research vessel, book a fly-in tour, or embark on a cruise.

Antarctic cruises vary widely in size and experience. The primary difference between large and small cruise ships lies in the level of intimacy and accessibility. Large cruise lines, such as Princess, Norwegian, and Holland America—which can carry several thousand passengers each—typically offer more amenities, including pools and entertainment. However, their size limits access to narrower passages and ice-choked areas.

Additionally, while large cruise ships are often the most economical option, they usually do not allow passengers to set foot on the continent due to passenger volume and strict Antarctic environmental regulations.

In contrast, small expedition ships typically accommodate 100 to 200 guests. They can navigate narrower waters and offer frequent landings and up-close encounters with wildlife. These smaller vessels provide a more intimate and eco-friendly way to explore Antarctica, as their reduced size minimizes their impact on the delicate ecosystem. They can, however, be quite expensive.

Popular small ship operators include National Geographic-Linblad Expeditions, Quark Expeditions, Swan Hellenic, and Atlas Ocean Voyages.

Cruising with Atlas Ocean Voyages

I traveled to Antarctica on a 14 day expedition cruise with Atlas Ocean Voyages. Atlas is one of a handful of companies that travels to Antarctica. The company has four ships, each capable of carrying 200 passengers. Expeditions with Atlas include a roundtrip charter flight from Buenos Aires to Ushuaia, a day tour of Tierra del Fuego National Park, and all excursions while on board.

Our ship—the World Navigator—left Ushuaia and traveled the Southern Ocean to South Georgia, before heading to Antarctica for three days.

Crossing the Drake

The 600-mile-wide stretch of ocean between Cape Horn and the Antarctic Peninsula is notorious for its unpredictable weather and some of the roughest seas in the world. Named the Drake Passage after explorer Sir Francis Drake, it is where the Atlantic, Pacific, and Southern oceans converge.

The Drake can be absolutely treacherous, with towering ocean swells, fierce winds, and crashing waves.

For those fortunate enough to encounter the “Drake Lake” instead of the “Drake Shake,” the journey can be surprisingly smooth. On our calmer days at sea, we enjoyed watching the albatross and petrels swoosh around our boat. We kept our eyes peeled for whales and dolphins and seals.

But the weather in the Drake Passage can turn on a dime.

During rough days, I mostly stayed in my cabin, nibbling on bread and vomiting over a trash can.

Our Landings

No two trips to Antarctica are exactly the same.

Throughout our cruise, our expedition leaders reminded us that the area’s harsh conditions and ever-changing temperatures could cause sudden itinerary changes. They encouraged us to be flexible, to expect the unexpected, and to keep an open mind.

As a result of this challenging environment, Atlas’ sub-Antarctic expeditions do not have a set itinerary. Instead, the captain and crew bring passengers to the best available landing spots given weather conditions, ocean swells, and time constraints.

We enjoyed five guided excursions during our trip to Antarctica.

These landings and zodiac tours brought us face to face with the continent’s striking scenery and wildlife.

-

Elephant Island

After two days of sailing the Southern Ocean from South Georgia, we reached Elephant Island—a remote destination in the Shetland Islands, made famous by the story of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Witnessing the historical location firsthand was both humbling and mind-boggling. Instead of helping me understand how Shackleton’s crew survived the expedition, seeing Elephant Island’s inhospitable terrain rendered the story even more farfetched.

Ernest Shackleton’s remarkable story is one of courage and perseverance and survival. An Anglo-Irish explorer, Shackleton led the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1914, with the goal of completing the first land crossing in Antarctica.

While navigating the Weddell Sea, Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, became trapped in fast-moving sea ice. Unable to dislodge the ship from the ice, Shackleton and his crew remained stranded. They withstood freezing temperatures and dwindling supplies for months.

The crew escaped their sinking ship by camping on sea ice until spring. Then, once temperatures began disintegrating the ice, the men loaded into lifeboats and set sail for Elephant Island.

From Elephant Island, Shackleton and five of his men set off toward South Georgia on a small boat called the James Caird. As they battled the stormy waves of the Southern Ocean for 17 days in search of help, the remaining 23 crew members—led by second-in-command Frank Wild—survived on Elephant Island for 4.5 months.

Not a single person perished.

A bust of Frank Wild sits on a small peninsula that has since been aptly named Point Wild. The monument stands as a tribute to the men who braved one of the most challenging survival stories in polar history.

Crashing waves made it impossible for us to land at Point Wild during our excursion, so we took in the view of Elephant Island and its chinstrap penguin colony from the deck of our ship.

-

Hydrurga Rocks

Hydrurga Rocks is a small rocky islet on Antarctica’s Palmer Archipelago. Named after the Hydrurga leptonyx, the scientific name for the leopard seal, the destination is an important habitat for seabirds and marine life.

Our time at Hydrurga Rocks consisted of both a landing and a short kayaking excursion.

When we booked our Antarctic expedition, we had the option of adding kayaking to our itinerary. Dan and I enthusiastically signed up, despite the additional $250 fee. We wanted t0 experience Antarctica from a different vantage point.

Once in our kayaks, we set out to encircle some of the area’s islets in search of wildlife. We watched a Weddell seal sunning on an ice floe, admired the active chinstrap penguins and nesting shags, and soaked in the tranquility of our surroundings.

While kayaking in Antarctica is a magical experience, partaking in the excursion means foregoing either a landing or a zodiac cruise. Dan and I were fine with that. We were confident that we would have other opportunities to set foot on Antarctica at a later time. Others in our group, however, were frustrated that kayaking meant skipping out on a landing.

As a result, expedition leaders chose to cut our kayaking session short in order to accommodate the wishes of the majority.

We spent the rest of our excursion on land, taking in the views of our surroundings and photographing the playful chinstraps up close.

Yet while stepping on Antarctica was exciting, Dan and I couldn’t help but feel disappointed. We had paid $250 to kayak and felt like we didn’t really get our money’s worth.

Luckily, the leaders took our feelings to heart and offered us a second complementary paddle later in the trip—generously enabling us to enjoy two paddles and a landing for the price of one.

-

Cierva Cove Zodiac

Our second outing on the Antarctic Peninsula consisted of a zodiac cruise around Cierva Cove.

A stunning spot at the northern end of Hughes Bay, the cove is home to a glacier face that regularly calves ice, resulting in a bay filled with floating bergy bits and grackle of all shapes and sizes. This calving ice creates large and small icebergs of all kinds—rough, smooth, and everything in between. The variety is mesmerizing.

The waters around Cierva Cove teem with life. We didn’t see any seals or up-close penguins during our excursion in Cierva Cove, but we enjoyed watching a group of four humpack whales near our boat.

Base Primavera is an Argentine research station established in 1977. It sits at the southern end of Cierva Cove and operates only during the austral summer.

We saw the fire-red huts of the research station from our zodiacs, but we didn’t visit the base itself. Nor did we check out the colony of gentoo penguins that we could see at a distance.

Instead, we cruised around the ice floes and soaked in the magnificent scenery. The cove boasts the most striking polar scenery that we witnessed on our 14 day cruise.

Portal Point

After visiting Cierva Cove, we had the opportunity to camp at Portal Point. The location would also be the site of our first excursion on the following day.

Portal Point was the first and only opportunity that we would have to make a continental landing. A striking wildlife-filled location near the famous Lemaire Channel, it was the site of a British research base during the 1950s. Though the base is no longer operational, the area remains a popular stop on Antarctic cruise expeditions.

Since Dan and I had chosen to sign up for camping on Antarctica, we didn’t mind skipping the following day’s landing at Portal Point.

So while most other cruise passengers made a continental landing at the location of our campsite, Dan and I were eager to explore the surrounding waters on kayaks instead.

Kayaking at Portal Point was an unforgettable experience. In a small group, we admired nesting shags, navigated shifting ice, watched icebergs calve, and kept a lookout for gentoo penguins.

The absolute highlight of our paddle consisted of watching a humpback whale up-close. The whale swam mere meters from our kayaks. It was both terrifying and exhilarating.

Couverville Island

Our last Antarctic excursion featured a zodiac cruise at Couverville Island.

A small rocky landmass within the Errera Channel, Couverville is particularly notable for hosting one of the largest colonies of Gentoo penguins in the Antarctic region. Tens of thousands of penguins inhabit the island’s rocky shores, while its waters teem with seals and whales.

Our zodiac cruise brought us along the island’s cliff faces, showing off thousands of penguins, nesting shags, and dramatic scenery. We admired snow petrels, kept a lookout for seals, and photographed icebergs.

In contrast to Hydrurga Rocks, where we’d gotten to see the gentoos up-close, our penguin encounters at Couverville Island remained at a distance. We saw snowbanks covered in black flecks and some groupings of penguins that were so dense that they seemed to coat the snow in black.

Since we visited the area in November, we were able to witness the area cloaked in dazzling snow. It was a brilliant white wonderland. The huge chunks of ice floating about the waters were every bit as impressive as the penguin colonies that we had come to see.

At one point, we nearly got trapped in rapidly shifting sea ice—a poignant reminder of the dangers of navigating the Antarctic waters.

Kayaking in Antarctica

Kayaking is an supplementary experience available (conditions permitting) on many Antarctic cruises.

Exploring the area by non-motorized boat allows you to soak in the content’s majesty from a different vantage point. You’ll be able to get close ice floes and take in your surroundings from water level.

While kayaking was a highlight of my time in Antarctica, you should be aware that the experience came as a tradeoff. You won’t be able to participate in landings or zodiac cruises if choose to kayak. In other words, despite costing extra, kayaking excursions are not supplementary experiences. They are simply a wonderful way of experiencing the continent in lieu of another (equally good) option.

The Polar Plunge

Can you really claim to have done a polar plunge unless you jump into the waters at (or near) the poles? I’m not sure.

But what I do know is that I wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to jump into the Southern Ocean.

On the last day of our voyage, about two thirds of the people on our ship took turns jumping into the frigid water.

The freezing point for ocean water is 28.8F, which is lower than freshwater due to salt content.

I’d be lying if I said I was excited to jump into the Antarctic waters. However, the promise of warming up in a hot tub and sauna afterwards gave me the courage to actually “take the plunge.”

I’m so glad I did.

It was exhilarating. Rejuvenating. A rite of passage. I 100% would do it again.

Camping on Antarctica

Why would we choose to pay money to camp on Antarctica when our ship offered a comfortable and warm place to sleep? That’s the question that many of the passengers on our boat asked the dozens or so of us who signed up to spend a night on the ice.

In truth, I wondered the same thing at first. Camping on Antarctica is an add-on experience that costs way more money than it should.

It was only when Dan proclaimed his intent to camp that I—not wanting to be outdone—decided to reconsider.

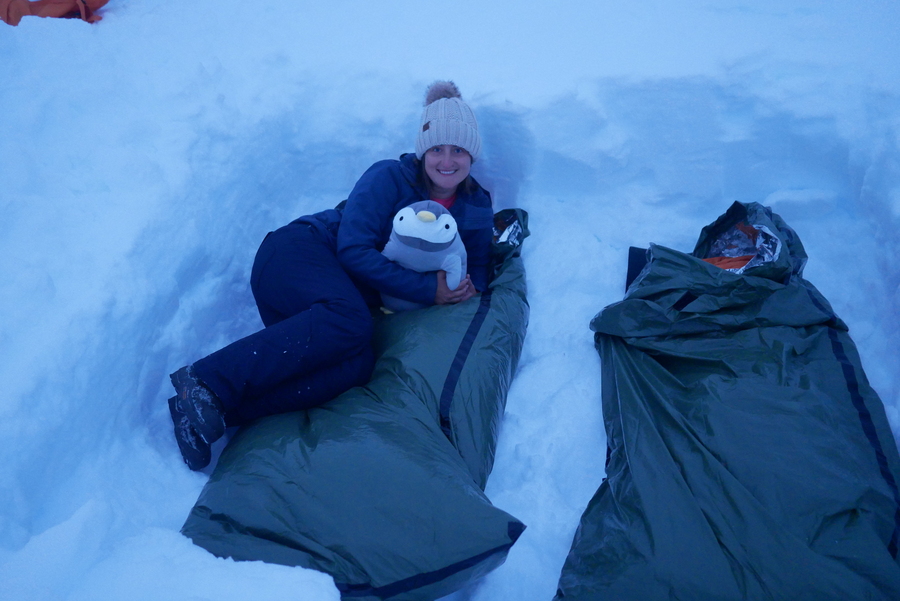

Camping regulations on Antarctica follow strict environmental guidelines. The Antarctic Treaty dictates that visitors leave no trace of their presence. Campers sleep on insulated mats and in specialized sleeping bags on the snow, often foregoing tents to experience the raw elements.

Our Antarctic camping experience began after dinner, when two of our expedition leaders brought us to Portal Point to set up camp.

Under the sky’s violet glow, we dug holes in the snow to shield us from the lashing winds. As we began digging, we heard a deafening roar. A huge chunk of ice near our site calved into the sea, bringing crashing waves onto shore. The thought crossed my mind that we were digging our own graves.

Luckily, the water from the waves did not infringe on our camp, but it gave us a jolt of adrenaline nonetheless.

I think the calving glacier was just Antarctica’s way of reminding us who was boss.

After we set up camp, we had a few moments to photograph our backdrop before burrowing in our sleeping bags for the night. The surrounding silence was profound. The sense of serenity, indescribable.

We took a moment to observe the world under Antarctica’s midnight sun. A lilac glow painted everything around us. In the water, we saw a leopard seal bobbing up and down. A solitary gentoo waddled over to see what we were doing, then plopped down near our campsite to keep guard.

In the distance, we could see our ship—a reminder that luxury and comfort was only a stone’s throw a way, no matter how hardcore we thought we were being.

Dan and I slept surprisingly well in our dug-out beds. Wrapped in our thermals and parkas and bivy sacks, we kept mostly warm throughout the night.

One lady in our group opened her eyes and saw the curious gentoo peering into her sleeping hole.

We woke up at 5am to a dusting of new snow on our sleeping bags. After dismantling camp and filling in our sleeping holes, we said goodbye to our snowy open-air hotel.

Two playful humpback whales escorted us back to the comforts of the World Navigator, where a buffet breakfast awaited us.

-

Is Camping on Antarctica Worth it?

I was skeptical as to whether camping on Antarctica would be worthwhile. The added cost ($500 per person) was a substantial price to pay, especially when tacked on to an already expensive cruise. I hear that the cost to camp with Atlas has now increased to $750.

If I return to Antarctica someday, I’ll probably choose not to camp unless I can do so for free. But I’m so glad I listened to Dan and chose adventure during our once-in-a-lifetime bucket list cruise.

In addition to bragging rights, our group of campers got to experience the White Continent’s wildlife and scenery on an intimate level. We saw a leopard seal, experienced a calving glacier, and made friends with a curious gentoo.

We got to spend extra time in a place that most people will never visit.

And for that alone, the experience of camping in Antarctica was 100% worth the cost.

Antarctica Trip Costs

Let’s get straight to the elephant in the room. Visiting Antarctica is expensive, no matter how you look at it. It is by far the most expensive single trip I’ve ever taken.

Antarctic cruises run between $6,000-$20,000 per person. Length of the cruise, month of the voyage, and expedition type all contribute to the cost.

Some large cruise companies afford the opportunity to view Antarctica on a budget, but if you actually want to set foot on the continent, you’ll have to join a pricier small ship expedition.

In general, February is the most expensive month to visit Antarctica. You can often find better deals by booking in March and November.

I’ve heard of some backpackers flying to Ushuaia in search of last-minute cruise deals. If you have a flexible schedule and plenty of time on your hands, it may be an option worth exploring.

I haven’t personally spoken with anyone who had success finding a last-minute cruise, but there are plenty of blog posts online outlining the process.

Antarctica Environmental Regulations

The Antarctic Treaty, drafted in 1991, designates Antarctica as “a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.” It prohibits all commercial mineral resource activities and sets strict guidelines for environmental protection.

The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) works closely with the Antarctic Treaty System to enforce tourism-related regulations. These regulations limit the number of visitors allowed onshore and restrict certain areas to prevent ecological disturbance.

A maximum of 100 passengers at a time are allowed to land at any given site on Antarctica. Ships carrying more than 500 passengers are not permitted to make landings at all, meaning those larger vessels offer only scenic cruising without disembarkation.

For this reason, small expedition cruises tend to be the pricier option when traveling to Antarctica.

Antarctica’s Wildlife

Wildlife-viewing opportunities on Antarctica rival some of the best on Earth.

Despite being a frigid land of extremes, Antarctica teems with animals that have adapted to its harsh conditions. Millions of penguins live on the continent’s rocky snow-covered slopes. Its nutrient rich waters are home to whales, seals, fish, and crustaceans. Beautiful seabirds soar overhead.

-

Penguins of Antarctica

Antarctica is home to four different penguin species: chinstraps, gentoos, Adélies, and emperors. On our expedition, we saw multiple large gentoo and chinstrap colonies. We did not see Adélies or emperor penguins.

Emperor and Adélie penguins are endemic to Antarctica and its surrounding islands. Some Atlas cruises visit Adélie colonies, but you won’t likely see emperor penguins on a trip to the Shetland Islands or Antarctic Peninsula.

The best place in Antarctica to see emperor penguins is Snow Hill Island in the Weddell Sea.

-

Seabirds of Antarctica

Beyond penguins, Antarctica is also home to an array of seabirds, including petrels, skuas, terns, and albatross.

The seabirds of Antarctica are a remarkable and resilient group, uniquely adapted to conditions of the Southern Ocean. They display incredible endurance, often traveling for weeks at a time above the open water in search of food.

Wandering albatross—a bird species that boasts the longest wingspan in the world—measure up to 12 feet from wingtip to wingtip. The striking seabirds glide effortlessly over the Southern Ocean for days without flapping their wings. Watching them circle our boat was always the highlight of our days at sea.

We also particularly loved seeing snow petrels and cape petrels during our visit to Antarctica.

-

Whales of Antarctica

The waters surrounding Antarctica are home to a rich diversity of whale species, drawn by the abundant krill in the Southern Ocean. Some of the most prominent species include humpback whales, minke whales, blue whales, orcas, sei whales and southern right whales.

During the austral summer, as the sea ice retreats, these whales migrate to Antarctic waters to build up energy reserves for their long migrations to warmer breeding grounds.

Peak whale-watching season in Antarctica is March, though you’re virtually guaranteed to see whales no matter when you visit.

-

Seals of Antarctica

Antarctica is home to five main seal species: Weddell seals, crabeater seals, leopard seals, Ross seals, and Antarctic fur seals. Weddell seals are remarkable for their ability to live further south than any other mammal, using their teeth to forge breathing holes in the sea ice. Crabeater seals, despite their name, primarily feed on krill. They are the most abundant seal species in the Southern Ocean. Leopard seals are top predators in the Antarctic ecosystem. Their powerful shark-like jaws swallow penguins, crustaceans, fish, and other seals.

Though the South Georgia portion of our trip allowed us to see fur seals and elephant seals in the thousands, we were far less lucky on the Antarctica leg of our trip.

I saw only two seals during my three days in Antarctica—a Weddell seal on an ice floe at Hydrurga Rocks and a leopard seal while setting up camp at Portal Point.

When to Travel to Antarctica

The best time to visit Antarctica is during the austral summer, which runs from late October to early March. During this period, temperatures are relatively mild and the region experiences nearly 24 hours of daylight.

Early in the season, during the months of November and December, the continent is dressed in its most splendid white attire. This is the best time to see icebergs and pristine snowy landscapes.

As the season progresses into January and February, Antarctica’s ice continues to melt. During the continent’s peak summer months, you can see hatching penguin chicks and encounter sunny skies. Receding ice allows ships to reach further south, revealing hidden inlets and destinations that are largely inaccessible during other months.

Most would argue that January and February are the best (albeit most expensive) months to visit Antarctica.

In March, whale sightings tend to peak, as whales feed in nutrient-rich waters before their migrations north.

We cruised to Antarctica in November and encountered wonderful weather.

***

There’s no other place on Earth like Antarctica.

A vast expanse of craggy mountains, cascading glaciers, and towering icebergs, the continent’s beauty is indescribable.

To reach the Seventh Continent means often contending with extreme temperatures, massive ocean swells, and ever-shifting ice.

It isn’t an easy voyage, but the intrepid nature of travel to Antarctica makes stepping on its rocky shores all the more rewarding.